- Home

- Justin Scott

HardScape

HardScape Read online

HardScape

HardScape

Justin Scott

www.seastoriesbypaulgarrison.com/benabbottmysteries.html

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright © 1994 by Justin Scott

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003100085

ISBN-10 Print: 1-59058-060-5 Paperback

ISBN-13 Print: 978-1-61595-060-8 Hardcover

ISBN-13 eBook: 978-1-61595-190-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

www.poisonedpenpress.com

[email protected]

Dedication

A. Lesile Scott

A series at last, Pop, home in our small towns

Epigraph

Hardscape

is what you see in winter

when flowers are dead and branches bare.

It forms the character of a house,

like the bones behind a face.

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

More from this Author

Contact Us

Chapter 1

I had a gut feeling that Alex Rose had not really driven his Mercedes all the way from New York to buy a weekend home in Newbury. It had been a while since I’d been a New York player, but, like my Armani suits mothballed in the attic, I had kept the instincts. I disobeyed them and offered to show him the Richardson place, hoping he was real. With the recession still twined around Connecticut, stubborn as poison oak, and the high-end country-house crowd pondering “fair share” taxes and hourglass loopholes, I had time on my hands and fifty listings for every buyer.

I drove him in my Oldsmobile, singing the praises of Main Street.

Our homes are set far back. A sweep of green grass separates curbs from sidewalks, and hundred-year-old elms and sugar maples arch overhead. Customers love it. It’s the street they had in mind back in kindergarten when they crayoned their first house with smoke squiggling from the chimney, a flower and a picket fence.

Rose sat silent as ice sculpture, blind to snug Colonials, elegant Federal mansions, snow-white churches, even our famous flagpole.

The only commercial structures in sight were the barn-red Newbury General Store, the Newbury Savings Bank, housed in a structure as conservative as its lending policies, and the picturesque Yankee Drover Inn. There was my Benjamin Abbott Realty shingle, and a couple belonging to my competitors. And that was about it, thanks to my grandfather, who wrote the zoning laws, and my father, who enforced them.

Modern conveniences, I explained—like the Grand Union, video rental, gas station, and the bikers’ bar—were hidden at the bottom of Church Hill Road. Rose grunted. I told him our flagpole was the tallest in Connecticut. He didn’t seem to care.

He was a big man who led with his belly, a well-fed forty-five or so, health-club tanned and burly, soft brown hair fertilized by Rogaine. Poring over my aerial maps, he had studied me with busy, hooded eyes.

He dressed like a house hunter, outfitted for “the country” in Bean boots and a corduroy shooting jacket with a leather rifle-butt patch and extra pockets for his bullets. He also looked like he could afford to buy, judging by the S-class land yacht parked at my office. So I kept driving and hoping.

Out of town, Route 7 runs along the river, matching it bend for bend with a forty-five-mile speed limit and dotted lines on the straights. I passed a Toyota loafing along at fifty, then slowed down for the Calvary Horse Farm.

“They give riding lessons for the kids,” I ventured.

“…Of course, there’s plenty of room on the Richardson place to keep your own horse. Ellie boarded some ’til she died.”

Four miles south of town I turned onto Academy Lane and, after a mile of it, onto a dirt road named Richardson Street, which was lined with ancient maple trees decaying from age, neglect, and the thrip. Still, they made a grand tunnel between two of the loveliest hayfields in the county.

“This used to all be Richardson land, but it’s been sold off. The house has six acres, with another fourteen available.”

Rose’s silence doomed his charade. Any buyer worth a mortgage would ask whether the open land would be developed with a bunch of tract houses. Ordinarily, my answer went, “Before 1990 I’d have had to admit development was likely. But those days are gone. The town will continue its very slow growth, but no big developments—Here we are!”

The neglected though elegant farmhouse was relatively new by Newbury’s calendar, built thirty years after the American Revolution. New wings and Greek Revival detail had been added on as Richardsons prospered, until the decline of New England farming left subsequent generations with a house too big to heat, much less paint. What had kept this faded beauty standing when many were lost was a New York City Richardson turned financier who had maintained it as an exquisite country home from the 1920s into the early 1960s. I directed Rose’s attention to the faint lines of brick paths through the thorn-tangled gardens. A cherry tree grew out of the clay tennis court, and the skating pond was reverting to marsh.

“Adlai Stevenson used to visit his mistress here. Or so they say. Her estate was out there, through the sycamores.”

Rose turned a full, slow circle, confirming we were alone. I pulled out my big ring of keys.

“There’s a beautiful brick keeping room that overlooks the skating pond. I swear on a winter day you can still smell the hot cocoa.”

“Do you know a lot of people around here?”

I told him I’d been born in Newbury.

“You know the Longs? Jack and Rita Long?”

I knew who he meant. And like everyone else I knew about the thirty-seven-room stone house they had built just across the Morrisville line, which people called “The Castle.” Fred Gleason had sold them a hundred acres and celebrated that winter in the Caribbean. The Longs had built in some sort of Victorian turreted style, with crenelations and, for all I knew, a moat of alligators. Jim York had decorated a few rooms. He reported that the Longs spent freely and paid their bills, sterling qualities in any client.

“Friends of yours?” I asked. “I’m surprised you didn’t ask Fred Gleason to show you houses. Fred was their agent.”

Rose pretended not to hear me. “He’s a guy about my size, dark hair, little mustache. Maybe a little overweight. She’s a terrific-looking brunette.”

“I don’t know them.”

It was none of Rose’s business that I had met Jack Long, briefly, and seen him in action at a land trust meeting. He had a firm handshake and looked you over real quick, pige

onholing you and assessing your worth. I thought he was a little pushy, throwing his weight around, and quick to remind people that, as a businessman, he knew “how these things work.”

On the other hand, Long was genuinely interested in the local effort to protect open space and had, I’d heard from Fred, put his money where his mouth was with a generous contribution to the buy-up kitty. Such is not always the case with the big bucks week-enders, so I had no problem overlooking his arrogance as typical busy-guy behavior.

The New Yorker had also, in the short time he’d been in town, become the hero of the guns-and-ammo crowd whose shooting range faced shutdown until he bought up adjacent property to prevent development of homesites in the line of fire. All in all, a man who got things done.

Rose wouldn’t let it go. “They come up on the weekends. Maybe you’ve seen them in town, buying the Times.”

I was tired of the game. “Assuming you mean what I mean by a terrific-looking brunette, I’m sure I’d remember meeting her. Are they the reason you’re looking for a house in Newbury?”

“Tell me about yourself.” The hooded eyes opened wide, hardening his big, blocky face.

I said, “I’ve got a better idea. Why don’t you tell me what you already know about me and I’ll fill in the spaces.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean you’ve dragged me out here under a pretext to talk about these Longs, which means you want something from me, because you think you know something about me. Tell me what you think you know.”

Rose planted his feet and folded his arms. His shooting jacket looked too new and a little silly. I was wearing my basic realtor’s uniform—chinos, a country-gentleman tweed jacket that looked thirty years old, and penny loafers with rubber soles for wet grass. I had a cap and windbreaker stashed in the car in case of a change in the weather.

We stood toe to toe a moment—an unarmed hunter and a country gent without estate—then Rose gave me a smirky wink that made his big face go lopsided like an eighteen-wheeler stopped on a soft shoulder.

“You asked for it,” he said, and, to my surprise and growing anger, recited my dossier.

“Benjamin Abbott III. You were born here, went to grade school here. Your old man ran the real estate office. He was also first selectman, which is sort of like mayor. You attended the Newbury Prep School, as a day student, then the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. You served in Naval Intelligence, resigned your commission when your obligation was up, went to work on Wall Street. Am I right, so far?”

He had missed twelfth grade when Great-aunt Connie persuaded my father to pack me off to Stonybrook Military Academy, ostensibly to prepare me for Annapolis, but mostly to keep me from getting into trouble with my cousin Renny. Renny was considered a bad influence, like “your hoodlum friend outside” in “Yakity-yak.” Only Renny and I knew it was the other way around.

Rose treated my silence to another smirk, and headed for the good parts: “On Wall Street you made a bunch of money running mergers and acquisitions, got nailed in the Michigan Machine insider trading scheme, and went to jail.”

“I didn’t break the law.”

“But you did time.”

“I sure did.” I felt invaded. He had slid a knife under a scar and peeled it.

“When you got out, you came home and took over your father’s business. His contacts put you first on line with the old money and the big estates that go to probate court.”

I wondered how a bloody nose would look on his shooting jacket. Rose backed up a step.

“Don’t you want to know why I’m telling you this?”

Of course I was curious why he’d driven a hundred miles to annoy me. “Not as much as you want to tell me.”

He backed up another step. His eyes got nervous, but before I could make him more nervous, he surprised me again. “I’m a private investigator.”

I had pegged him for a lawyer, from his bad manners and his car. He could have been a doctor, but the Mercedes did not have MD plates. And I knew he wasn’t a Wall Street guy; they’re friendlier, salesmen at heart. I was a salesman at heart. But I wasn’t feeling friendly. “Who’s paying you to dredge up my past?”

“I’m offering you a job.”

“A job? What do you mean, a job? Doing what?”

“Mr. Long is my client. I want you to shoot a video of Mrs. Long screwing her boyfriend.”

I laughed.

“You think I’m joking?”

“I always assumed there were professionals who did that for a living.”

“There are, and were she balling this guy in New York I would employ them. But I don’t know anyone I can trust to go rooting around up here in the woods without getting caught by the local cops.”

“That’s not a problem,” I said. “We have one resident state trooper to patrol sixty square miles of township. Tell your people they’re safe as long as they don’t fall into his radar trap.”

“I’m serious,” said Rose. “The Long house is way out in the boonies. I need a local man. A real ‘woody.’ I’ll pay you two thousand dollars for a half hour of clear videotape.”

“Two thousand?” I laughed again. “I’ll introduce you to a woody who’ll do it for two hundred and burn the house down for another fifty.” I had in mind one of the Chevalley boys.

“I want a man with a head on his shoulders, not some damned redneck swamp Yankee.”

He was mixing his regional slurs. I let him, just as earlier I had not interfered when he mispronounced Newbury like the fruit instead of the cheese. Neither a berry nor an event in a graveyard, we are, properly, Newbrie.

“I’m not a cameraman.”

“It’s just a Sony camcorder. A kid could use it.”

“I’m trying to tell you as clearly as I can that I’m not interested in taking dirty pictures.” Actually, I was intrigued. I could certainly use two thousand dollars, and playing detective sounded like fun, provided one didn’t break one’s neck falling off the lady’s roof. But I had enough troubles, reputation-wise, without it getting around town that Ben Abbott had turned into a Peeping Tom.

“Three thousand dollars.”

I walked to my car. “I’ve got to get back to town, Mr. Rose.”

He got in and we drove out of there, and it was my turn to be silent. Rose got talkative. He remarked on the trees, the river, the horses, even the hard kick in the back when I passed a station wagon on a short straight. “What kind of car is this?” This last, an artless prelude to fulsome praise, as its name was printed in raised letters on the dashboard.

“Oldsmobile.” Cars I would talk about.

“I didn’t realize they were so powerful.”

“Caddy engine. Bored and stroked. Eats BMWs for breakfast—Son. Of. A. Bitch!”

“What’s wrong?”

I slowed down and pulled over, my mirrors sparkling like the Fourth of July. Trooper Oliver Moody, who should have been down at the high school at this hour instead of hiding behind a Northeast Utilities truck, swaggered out of his state police cruiser, already writing the ticket with my name on it that he kept in his glove compartment. He danced me through the procedure, enjoying every moment, handed back my license and registration, and advised me I could pay the eighty-dollar fine at Town Hall.

Rose said, “I thought they didn’t ticket locals.”

“We’re not friends.”

Oliver burned rubber out of there with an ironic salute, and I continued driving, silently, into town.

“I know what you’re thinking,” said Rose. “You’re thinking that back when you worked on the Street three grand was chump change.”

Actually, I was thinking I could get the barn winterized.

At the flagpole, Rose said, “Four thousand dollars and that’s my final offer.”

The money was sounding better and better. I couldn’t deny I could use it. Nor could I deny the occasional restless night when Newbury was quieter

than death and my decision to come “home” to put my life back together seemed a sort of voluntary house arrest. I was far from saying yes, but why not pump Rose a little to find out what was going on?

“I ask you again, why me?”

“For crissake,” Rose exploded. “You want me to paint a picture? Mr. Long goes first class. He believes that he gets what he pays for. He doesn’t question my fees, he only expects me to get the job done. He can afford it. Are you beginning to register what I’m talking about?”

“You bill him cost-plus.”

“Exactly like you when you ran leveraged buyouts. There’s so much money flying around who’s going to question fees?”

“And I’m ‘first class’ because I went to prison?”

“The word is you did time because you wouldn’t rat on your friends. Loyalty’s valuable. The fact you got out alive says you learned to handle yourself. That’s an asset, too.”

“Tell your boss if he ever finds himself in a similar position, treat it like Outward Bound.”

“The jail thing is my opinion. What turns Mr. Long on is your ONI background. He ate that up.”

“It takes a civilian to really appreciate the military.”

“He fought in ’Nam.”

“Tell him I spent most of my time investigating sex-bias complaints.”

“Terrific training for P.I. work—you could probably get your license. Wha’d you investigate the rest of the time?”

I didn’t answer.

“Thought so,” said Rose. Another eighteen-wheeler wink implied we both knew that real men do not betray secret submarine landings on the Baltic Coast. For all his heavy-handed flattery, I still wasn’t a hundred percent sure why he wanted me. That might be part of the fun. And I had a feeling if I opened the door without speaking, he’d up his offer.

I opened the door.

“Five thousand.”

Chapter 2

The wildest thing my father ever did in his good and orderly life was marry my mother, Margot Chevalley—bastardized “Chevalier” in New England, where folks never needed black people to dump on because they already had the French.

FrostLine

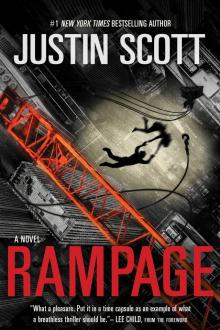

FrostLine Rampage

Rampage McMansion

McMansion Mausoleum

Mausoleum HardScape

HardScape The Shipkiller

The Shipkiller StoneDust

StoneDust