- Home

- Justin Scott

The Shipkiller Page 2

The Shipkiller Read online

Page 2

Part of his mind exclaimed at its smoothness. Not a seam or a rivet protruded from the polished surface of the sheer wall. His head kept going underwater and he realized that the propellers were pulling him down.

Frantically he kicked off from the passing hull, but each time he started to swim away it drew him back to the long, straight vortex of rushing water between the ship and ocean. Again and again he tried to swim away, but each time he was drawn back until, surrendering to exhaustion, pain, and fear, he struggled only to protect his body from the metal.

It slid past for so long that he began to think he would be trapped forever between a moving wall and the sea. Each time he kicked, its forward motion spun him partway around and slammed his back into the hull. Had it not been for the bulky life jacket, he would have been battered to pulp. As it was, his knees and elbows were smashed horribly.

Suddenly it was gone and he was hurled into froth and foam that filled his nose and mouth and stung his eyes. He sank beneath the surface, the life jacket useless in the aerated water that the ship’s propellers flung behind it. The froth entered his lungs; he coughed and retched as the heavy salt water pierced the membranes of his mouth and throat.

The froth congealed into liquid. The sea subsided. The life jacket brought him to the surface. He was alone on a piece of water as flat as a pond. A huge square stern was vanishing into the cloud. Above it was an enormous white bridge, topped by a pair of straight black funnels belching gray smoke. The air reeked with exhaust, but under that smell was the strong odor of crude oil.

Lettered across the black stern in stark white was the name of the ship: LEVIATHAN.

Beneath its name, its home port: MONROVIA, LIBERIA.

“Carolyn!” Hardin yelled.

He threshed around looking in every direction, but saw nothing. As for the ship that had run him down, it was gone, vanished in the cloud. Slowly the sea came back. Waves entered its wake, tentatively at first, as if fearing its return, then with vigor, more and more boldly, until Hardin was bobbing from low troughs to high crests, screaming Carolyn’s name, and trying to raise himself out of the water to see farther.

The cold was fierce, anesthetizing the pain in his elbows and knees, numbing his mind and body. Mists swirled closer, narrowing his view. He was slipping into shock when his hand hit something solid. He flinched with terror. Sharks.

Kicking and splashing, he heard his own voice yell like an animal’s. He felt the terror take his body back from the realm of shock. Instincts assumed command. He reached for the knife that hung from his life jacket and tucked his aching knees until he was bobbing like a ball.

It hit him again, and again terror wrenched his stomach. It was on the surface. His hand closed on something. He brought it to his eyes. A splintered piece of wood. Teak. Part of the cockpit coaming.

Other objects bumped against him. Wood, Styrofoam.

“Carolyn!”

A shape rose suddenly out of the fog. White and bulbous. He swam toward it, knowing nothing more than that it floated. The life jacket confined his strokes, so he extended his arms like a prow and kicked with his feet, his knees paining. The object glided away on a wave. Hardin forged after it, lunged, touched it. His fingers slipped on the slimy surface. He recoiled from the impression of living flesh.

Then he recognized Siren’s dinghy. Or half of it, sheared in the middle as if cut with a knife, and floating upside down, kept buoyant by its Styrofoam packing. He gripped the broken end.

If he could turn it over and get in, he could search for Carolyn from its greater height. He stretched his arms and gripped each gunnel. Ignoring a new shooting pain in his right elbow, he kicked to maintain leverage and pulled down on one side of the shattered boat and pushed up on the other. It tipped partway before escaping from his hold.

Hardin swam after it, reached over its bottom, and tried to hold its stubby keel. Again, as it tipped toward him, he couldn’t maintain his grip. He worked around to the broken end and tugged with all his strength on one side. Slowly, he got it to dip underwater. Then the buoyant Styrofoam refused to sink farther. He brought his feet up, jammed them against the inside of the gunnel and threw his entire weight on the broken dinghy. It flopped upright.

Hardin tumbled backward and broke surface, retching and coughing, the salt stinging his throat and eyes. He spotted the dinghy and swam after it. Its stern floated high while the open end was underwater. Reaching the open end, Hardin turned around and tried to sit on the bottom. The dinghy threatened to flip back over. He reached farther back, grabbed the interior braces and hauled his buttocks into the bottom of the boat. The stern rose higher. Letting the waves assist him, Hardin inched farther and farther into the shattered hull until, at last, he was propped in the stern, half seated, waist deep in water, his feet dangling over the break. He drew them in, still afraid of sharks.

“Carolyn!”

The dinghy lurched. It was like a shallow bowl. It would support his weight until he tried to move. Then it tipped dangerously and threatened to fling him back into the ocean. He experimented cautiously, moving his body until he had propped his shoulders against the transom so he could see over the sides.

The fog and rain clung close to the surface, offering less than fifty feet of visibility. He saw the debris of his boat, pieces of the teak decks, a cupboard, some shredded sailcloth. Had it been ground up by the ship’s propellers?

Siren’s fiberglass hull would have sunk quickly. He shivered. It was probably still sinking, with a mile or two yet to fall before it touched the cold, muddy floor, the enormous water pressure crushing the light bulbs. The cabin lights and reading lamps first, then the smaller, tougher globes in the running lights.

“Carolyn!” He caught a glimpse of the front half of the dinghy. He strained to see more clearly. Had she gone to it the way he had gone to his half? A current swirled it around, revealing the gaping emptiness of the shattered hull. It drifted from his sight.

He called her again and again and cupped his ears for response. Nothing. He raised his head as high as he could and scanned the shrinking circle of his vision. It was getting dark. Had she lost her life jacket? Was she sucked beneath the ship? Was she a hundred feet away, unconscious? He called her name for hours.

3

The Ultra Large Crude Carrier LEVIATHAN was the biggest moving object on the face of the earth. It carried one million tons of Arabian oil, and it drove through the ocean like a renegade peninsula.

The seas that Siren toiled up and down were nothing to the gigantic ship. Its blunt bow smashed them like a battering ram, and its square stern laid the North Atlantic as flat as a sheltered bay.

LEVIATHAN was one thousand eight hundred feet long—over a third of a mile—so long that in squalls its bow was invisible from its bridge. It was so wide that the distant smudge glimpsed earlier on the horizon, which Peter and Carolyn Hardin had reckoned was the side of a passing ship, had been in fact LEVIATHAN’s bow pointed straight at them.

Two days later—during which time LEVIATHAN had off-loaded at Le Havre and begun its return voyage to the Persian Gulf—two elderly and relatively small hundred-thousand-ton oil tankers brushed hulls in the crowded English Channel. There was no explosion and damage was slight. The empty ship, outbound in the proper traffic separation lane, proceeded into the Atlantic, effecting repairs as she went. The inbound ship, fully laden and conned by an aging master who preferred to ignore traffic schemes, suffered a number of crushed hull plates and leaked some cargo. The spill was less than two hundred tons.

The floating oil blew onto the coast of Cornwall, where it caught several thousand migrating gulls resting on the beaches. Fishermen, farmers, shopkeepers, and painters descended the rocky cliffs and collected the victims, which were poisoning themselves by preening the crude oil from their feathers. The people set up a field station to remove the oil and keep the birds warm until they had dried.

Dr. Ajaratu Akanke, a young African woman, joined the rescue late in the a

fternoon when her hospital shift had ended. By then the beach was littered with dead birds and the cries of the living were growing faint. She had done this before, and when she saw that most of the birds left were dead, she walked beyond the main slick, which had covered the pebbles with several inches of sticky tar, and searched where no one had had time yet to look.

She was tall and very dark, with high cheekbones and a narrow nose and delicate lips that spoke of an Arab or Portuguese slaver generations back in her family. A plain gold cross hung from her neck on a slender chain.

She found a cormorant wedged between two rocks where the tide had left it. Its eyes blinked dully through the thick crude that coated its head and body. The diving bird had apparently surfaced in the slick. There was no doubt it would die, so she snapped its neck with her long, graceful fingers.

She put the corpse in a plastic carry bag, so the oil wouldn’t kill a scavenger, and looked for more birds. About a mile from the main body of searchers, she rounded a high rock flecked with oil and stopped short. A man, half naked, in a yellow life jacket, was lying on the pebble shelf, his legs white, the skin shriveled from long immersion. She knelt beside him, expecting more death.

Hardin awakened clearheaded. He knew he was alive. He knew he was in a hospital. He guessed from her manner that the striking black woman standing next to his bed was a doctor.

She was counting his pulse from his left wrist. Her cool fingers had broken his sleep. She said, “Good afternoon,” in a cultured, upper-class British accent.

“Where is my wife?”

“I’m sorry. You were found alone.”

Grief ripped through him. “What day is it?”

“Thursday.”

It had happened Sunday. “Did they find her body?”

“No.”

“Maybe . . . Where are we, England?” he asked, prompted by her accent and his memory of Siren’s position rather than his surroundings. It was a bright, airy room; his was the only bed. There were windows on two sides and sheer white curtains blew tropically in a light, warm breeze.

“Fowey, Cornwall,” said the woman. “On the Channel coast. I found you on the beach.”

Hardin sat up and tried to swing his feet off the bed. His right knee wouldn’t move. “Maybe she’s farther down the coast. Did anyone else find someone?”

“No, I’m sorry.”

“Maybe a boat,” he said, ransacking his mind for hope. “Maybe the French.”

The woman placed coffee-black hands on his shoulders and firmly pushed him to the pillow. She said, “The authorities are all aware that a man was found at the edge of the sea. Where you’ve come from no one knows, but they trade information. Had a woman been found, alive or dead, they would know.”

Hardin tried to resist and found he was too weak. The outburst left him trembling. He sagged back on the bed, his eyes half closed, a dark, empty space expanding in his heart. It was more than he could bear and he took refuge in inconsequentials.

“I’m a doctor,” he said. “I’ve suffered a mild concussion.”

She eyed him cautiously. “You’ve been unconscious for a full day here. How long were you in the water? What happened?”

“In that case,” amended Hardin, concealing a stab of fear, “I’ve suffered a severe concussion. I was last conscious Sunday night. . . . Skull fracture?”

“No.”

“Projectile vomiting? ”

“Not yet.”

“Respiration?”

“Normal.”

“Is that why you didn’t tube me?” Throat and nose tubes were ordinarily inserted into unconscious patients to prevent respiratory blockage.

“I, or a nurse, was with you at all times. I would have employed tubes if you had remained unconscious much longer.”

“I’ve been sleeping off the exposure,” said Hardin.

“Perhaps.” She wiped his forehead with a cool cloth. “What is your name?”

“Peter Hardin.”

“I am Dr. Akanke, Dr. Hardin. I want you to sleep.”

“Please.”

“Yes?”

“Seven degrees, forty minutes west. Forty-nine, ten north. My nearest last position. Tell them to look for her somewhere around there, please.”

She made him repeat the numbers. He thanked her, then followed her with his eyes as she glided from the room. His gaze shifted from the door to one of the windows. The breeze pushed the curtain aside. He saw the sea, green and sparkling, far below.

He awakened in the dark, his scalp prickling. He tensed, waiting for the movement to repeat. It was coming again. He sensed it, couldn’t see it, but he knew it was moving. It was black. It was coming straight at him. He sprang off the bed. One of the windows was wide open. It reached the floor. He ran through it. The black followed, flanking him. He ran and was suddenly in the water where he couldn’t move fast enough. The black advanced, pushing a white wave before it.

Hardin yelled.

He heard a soft sound and felt safe. Dr. Akanke’s face was close to his. Her voice was liquid smooth.

“A nightmare, Dr. Hardin. You’re all right now.”

The harbor master kept calling him Lieutenant, because Hardin had mentioned in the course of the lengthy interrogation that he had served as a lieutenant aboard a United States Navy hospital ship. He was an old man, and despite his pleasant manner was clearly incredulous.

When Hardin realized that he was about to repeat all his questions for the third time, he said, “You don’t believe me.”

The harbor master shuffled his notes. “I hardly said that, but it is rather incredible, now that you mention it.”

“I’m lying?”

“Your memory . . . your injuries . . . Dr. Akanke says you have a concussion. . . . I’m not—”

“I saw the name on the stern.”

“You could not have survived,” he said flatly.

“I did survive,” said Hardin. “A ship named LEVIATHAN out of Monrovia sank my boat and killed my wife.”

“Lieutenant, LEVIATHAN is the biggest ship in the world.”

“You’ve said that three times,” Hardin yelled. “What the hell am I supposed to do about that?”

The harbor master made clucking sounds and backed from the room. “Perhaps when you feel better.”

Hardin swung his feet off the bed and half rose. Shooting pains locked his knee. He fell back, his face contorted. The old man looked alarmed. “Lieutenant?”

“Was LEVIATHAN in the area in which I was found?” Hardin asked quietly.

“It off-loaded at Le Havre on Monday night. Still, I feel . . .”

“Get the hell out of here,” Hardin said savagely.

The local police inspector was a youngish, intelligent-looking man with a sympathetic smile and cool eyes. He began with a grim assurance.

“I’m sorry, but there’s been no sign of your wife. We’ve doublechecked the Channel ports and are in communication with the French and Irish.”

“She could have been picked up by a boat without a radio.”

“Unlikely.” The inspector leaned forward. “Now, Dr. Hardin, we have to verify who you are. Whom do you know in England?”

Hardin mentioned a few London doctors.

“We would like to fingerprint you.”

“Who the hell do you think I am?” The pain in his knee was making him irritable, but he agreed with Dr. Akanke that his head trauma precluded the use of pain medication.

“This harbor is a port of entry,” the inspector replied blandly. “We are often unwilling hosts to Irish gunrunners, drug smugglers, and all sorts of illegal aliens—Paks, Indians, what have you.”

“Which do you think I am?” Hardin asked angrily, focusing his hurt for Carolyn. “A Pakistani or an IRA terrorist swimming ashore with a howitzer in my teeth?”

“That’s quite enough for one day, thank you, Inspector,” said Dr. Akanke. She had been waiting at the door. Now she swept into the room, flanked by two nurses who guided the

policeman out. As soon as he had gone, she put a thermometer in Hardin’s mouth and said, “You’re in no condition for shouting.”

It was a day since he had awakened in the hospital. The harbor master and the police officer had stirred a deep anger that had begun to smolder inside him.

“I want to call New York.”

“I suggest sleep. We’ve already contacted your embassy.”

“I’ll sleep after I call my attorney, Doctor. Would you please arrange it? ”

She bridled at his tone.

“Please,” said Hardin. “I’m very upset. There’s somebody I have to talk to.”

“Very well.”

Twenty minutes later an attendant arrived with a telephone on a long extension cord. The overseas operator verified each end of the line and told them to go ahead.

“Pete,” said Bill Kline. “What the hell is going on? They said something—”

“We got run down by a ship.”

“You okay? ”

“Carolyn’s missing.”

“Oh Jesus Christ! How long?”

“Five days.”

“Oh,” Kline moaned. “Oh, no. . . .” The line hissed quietly for a while. “Is there any chance? ”

Hardin took a deep breath. He couldn’t lie anymore. The water was too cold. He himself had survived by a miracle. Another wasn’t likely. “Not much of a chance . . . none.”

Hardin closed his eyes and listened to his friend sob. Kline had worshiped Carolyn. He had contributed to the ruin of his second marriage by comparing her to his own wife.

“What happened?” he asked.

“We got hit by an oil tanker. LEVIATHAN”

“LEVIATHAN? Jesus Christ, didn’t you see it?”

“It came out of a cloud bank wide open. We didn’t have a chance.”

“Weren’t they using radar? ”

FrostLine

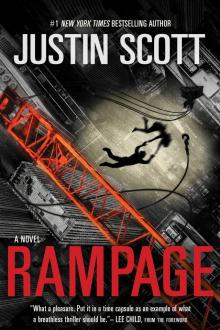

FrostLine Rampage

Rampage McMansion

McMansion Mausoleum

Mausoleum HardScape

HardScape The Shipkiller

The Shipkiller StoneDust

StoneDust