- Home

- Justin Scott

HardScape Page 5

HardScape Read online

Page 5

“Sure does.”

The kitchen was the sort you find in houses owned by people with endless bucks—the latest everything, the air vibrating with the ceaseless hum of electric motors. It was spotless, with takeout menus from Church Hill Road Shanghai Cafe and our matchless Lorenzo’s Pizza Palace on the refrigerator.

The house did not have quite the rumored thirty-seven rooms, but there were three beautiful guest-room suites upstairs and a spectacular master bedroom with a fireplace and his and her bathrooms and his and her walk-in closets and a little attached sitting room-television room also with a fireplace. The bed was magnificent, with French-Canadian antique ironwork at the head and foot, and it would have taken a better man than I not to imagine the matchless Mrs. Long sprawled upon it, smiling through a veil of raven hair.

I could not resist asking, “What’s down that hall?”

“Just my studio.”

“Do you want me to look at it?”

She hesitated. “Sure. Just a second.” She ran ahead, and when she called, “Okay, now,” I walked into the white studio and saw she had draped the smaller easel as well as the big one.

“Works in progress?”

“Progressing slowly…So? What do you think?”

“I think you have a lovely house. And I’m sure I’m not telling you anything you don’t know when I say there are a limited number of buyers for such a place.”

“If you were handling the sale, what price would you ask?”

“Well, I’m not handling the sale, but if I were…four million.”

“And what would you advise me to take?”

I hesitated. Then I asked, “Are you in business? Or are you a painter?”

“I’m not a painter.”

“This looks like a painter’s studio,” I said.

“I play when I get time. No—to answer your question—I work closely with Jack. I know about business.”

“So I’m not talking to a babe in the woods.”

She still didn’t flirt, but she did smile. “That depends on whose woods.”

“We’re just talking—just us—but you ought to know that the lowest number you allow to be mentioned in a conversation with your realtor is very likely the number he’ll bring you in the end.”

“Okay.”

“I wouldn’t take a penny under three million. And I’d fight like hell for three-five.”

“Even in this climate?”

“Especially in this climate. You’ll get some sharpy out here figuring to pin you to the wall—but he’ll have the bucks, and if his wife gets a load of this place he’ll pay you three-five or she’ll stop sleeping with the louse.”

Mrs. Long laughed. “I get it. Thanks. Come on, we’ll have that drink.”

We got down to the kitchen and she said, “Any objections to champagne?”

“None.” I smiled back, thinking I couldn’t imagine a lovelier end of the day, or beginning of the evening.

She filled a silver icebucket and dunked the bottle. Then she got a pair of flutes and said, “Grab that, if you don’t mind. We’ve got a great place to drink it.” She led me down a hall through a massive oak door to the foot of a narrow spiral stair that led up into the turret.

I smelled gunsmoke.

I said, “Your husband been shooting deer again?”

“No, he set up some targets last weekend. Deer size and shape but only paper.”

It smelled more recent, to me.

I followed her pretty bottom up the stairs, flirting with a fantasy that she had broken up with her boyfriend after Trooper Moody and the burglar people left, sent him back to New York, and now felt the need of being consoled. This fantasy worked best when I ignored the fact that they had been playing hide and seek at the Newbury Cookout four hours ago.

Up and up we went, round and round, our footsteps on the metal steps echoing off the stone walls. Higher and higher, until right under the conical roof we came to a little round platform just big enough for a couple of small chairs and a table for our glasses. I put the bucket on the floor and sat down when she did.

“Would you open it?” she asked.

I peeled the foil and the muzzle, freed the cork with a modest pop, and filled our glasses. She touched hers to mine and met my eye. Her expression was clear, open and content. “Isn’t this great?” she asked, and I knew in that moment that she was simply happy to have me as a guest in her house.

Directly in front of us was an opening wider than the bowmen’s windows. Through it we could see for miles, a view like a Dutch or Hudson River School landscape, hills and trees and meadows, all in the fading light of a September evening.

That part of me that won’t let things be asked, “How could you sell it?”

She drank deep, and I regretted asking, because quite suddenly she was not content. The idiot she had treated so hospitably had just reminded her of a conflict tearing her life apart. At least that’s how I interpreted the pain that shadowed her eyes. She looked down, stared into her glass, and said, “Everything’s a tradeoff.”

It occurred to me that the Longs might have gone broke. The Castle wouldn’t be the first great house to mask its owners’ private desperation. But knowing more about her than I had any right to, I figured she was more likely considering leaving the husband, and the money, for the boyfriend.

I wanted to warn her that her husband knew. The question was what loyalty—or discretion, at least—did I owe Alex Rose. I had, after all, accepted his job and his money. Did quitting absolve me?

I looked at her, and she looked away and stood up and moved to the opening in the wall. She stared out. I drank champagne. Suddenly her whole body stiffened. She thrust her head and shoulders through the opening in the stone, straining to see.

“What’s that?”

I stood up beside her and looked where she was pointing. The sun had deserted a meadow but for the eastern edge along the woods, and there in the last rays something gleamed white. It was quite a distance away, and yet I could sense it shiver when the wind riled the grass around it.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Looks a little like a deer’s white tail, but they don’t lie down in the open, and certainly not at this hour. It’s feeding time. You’ve never seen it there before?…Maybe your husband shot another one.”

“No,” she said impatiently. “He’s away.” She turned to the stairs, worried, and said loudly, “I have to see what it is.”

She started down the metal steps, fast. I left my glass and followed. Down the steps, my hurt knee locking, through the big door, down a hall, and into the kitchen and out the back door. On the lawn she broke into a run. I limped after her, to the edge of the meadow. She plunged into the higher grass before I could warn her about the deer ticks. I stopped to pull my socks over my pants and trotted after her. She could shower off later. I could dry her back.

She crossed the meadow, exactly where I had trod last night, and up the slope to the woods. Suddenly she slowed, then stopped, rigid, and put her hand to her mouth. I caught up. The white thing blowing in the wind, gleaming in the sun, was hair. Blond hair. Her boyfriend was sprawled on his back, with a brick-size bloody exit wound where his muscular chest had been.

Chapter 6

There’s truth in the cliché that people seem to shrink when they die. My father’s body had looked hollow at Butler’s Funeral Home; by the time we got him to the churchyard he was almost transparent. A prisoner I saw shanked—a big man—fell like laundry. Mrs. Long’s boyfriend was different—robust—drinking in the sky with wide-eyed wonder. I remember thinking that the last innocent had escaped the planet, and those of us still stuck here were the dead ones.

His name was Ron; she kept calling him Ron as she knelt beside him and took his body in her arms. I reached to comfort her and lead her away, until I thought, Wait, this isn’t television, let the poor woman grieve. I backed off, and stood guard, or something, at a distance.

> It could have been a hunting accident. Some damned fool poaching out of season, spotting the white flash of Ron’s hair, mistaking him for a whitetail deer. It happens, both in season and out, though most often when they issue doe licenses, because then the hunter doesn’t even have to try to confirm he sees the buck’s antlers. Just spot a white tail and blast away—Oh, my God, it was my kid; or my father; or my cousin. Or my wife. (Sometimes called a country divorce.) High-powered weapons, low IQs, and plenty of booze; little wonder we have too many deer.

I wished I hadn’t smelled the gunsmoke in the turret.

It would be dark soon. I really should call Oliver. But Mrs. Long—Rita—she just wasn’t going to be Mrs. Long for me any more, or anyone else, when it was established Ron was on the property—Rita was still holding him, still whispering in his dead ear.

Poachers tend not to have hunting accidents. They are, in their way, professionals. A woody who puts deer meat on his table, or earns some spending money selling to butchers, usually treats guns with the respect they deserve. I’m not saying that a Chevalley boy—or one of the Jervis clan—would never have an accident poaching, but it’s less likely. Still, Oliver Moody and the state police investigators would be combing the woods for evidence. As soon as I called them.

I went back to Rita and said, “Mrs. Long, I’d better call the police. Are you all right here, or do you want to come with me?”

“I can’t leave him here.”

“I’ll come back with a blanket.”

“No. I can’t leave him here.”

I misinterpreted her to mean that Ron’s body should not be found on her property, which struck me as both unrealistic and surprisingly cold. I said, “We shouldn’t move him. The police have to investigate.”

“He’s dead. It doesn’t make any difference. Help me get him inside.”

“Inside?”

She took my heart again.

“There’ll be animals at night. It’s getting dark. I don’t want him hurt any more.”

I wished to God I could make things right for her. “I’ll call the police and I’ll come right back with a blanket and flashlights and we’ll stay with him until they come.”

Halfway to the house I looked back. She was dragging him through the grass. “Christ!”

I ran to her. The damage was done. She’d gotten her hands under his arms and had somehow moved him ten feet from where the bullet had killed him. She was breathing hard, gasping with each step. The expression of total concentration on her face said there wasn’t a thing she wanted to do other than get her man indoors.

I took one shoulder and arm, she the other, and we pulled him through the grass, his heels beating a path, the blood trailing down his pinstriped shirt and spilling under his belt. On the mowed lawn, I knelt, worked both arms under him, and carried him, cradled. Rita held his hand, letting it go only to open the front door. At her direction, I laid him down on a couch in the living room. It was upholstered with a silk brocade, but I knew enough not to suggest a towel. She arranged his arms and legs, and when she had him lying there as if he’d dropped off for a nap, she knelt on the Persian carpet, put her head on his shoulder, and wept.

I went into the kitchen and telephoned Oliver.

“What do you want?”

“A guy’s been shot at the Long place.”

“Dead?”

“Yes.”

“Who shot him?”

“I have no idea.”

“Who’s there, now?”

“Just me and Mrs. Long.”

“Don’t touch a thing.”

***

Angry, Ollie looked even bigger. “I told you not to touch anything.” He stood close, muscles gathered, ready to throw a punch.

“You told me too late.”

“You moved the goddamned body. You’re impeding an investigation.”

“It’s done.”

“Done, hell. I’ll charge you.”

“You want me to show you where we found him, while there’s still light enough to see?”

He did. We walked across the lawn and through the meadow, Oliver fuming at the track we’d scored in the high grass. “Jesus, Ben, you’ve pulled some dumb stunts in your life, but this one takes the cake.”

“We found him there.”

“Stand back.”

He strung yellow crime-scene tape in a fifty-foot circle around Ron’s blood. It had looked to me when I first saw the body that Ron had fallen dead and hadn’t moved an inch; now, who knew? Rita and I had flattened the grass. Oliver stayed outside the tape, and scanned the dark woods.

“What were you doing out here?”

“Appraising the house.”

He took off his mirrored glasses and fixed me with his pale gray eyes. I had always preferred him in sunglasses. His eyes were reptilian: cold, and stupid. Komodo dragons are stupid, too, but they eat mammals.

“Appraising the house or appraising the wife?”

“Appraising the house.”

“Did you know the guy?”

“No.”

“Did she?”

“She didn’t say.”

“So why’s she bawling?”

“She didn’t tell me.”

I supposed I’d be wise to cover myself in advance by relating last night’s fiasco—bring it up before they back-tracked to Alex Rose through Mr. Long, Rose saying, Oh, yeah, I paid a local bumpkin to film them screwing. Ask him—he’ll confirm they were lovers—but that reeked of snitch. I was caught in the middle. I couldn’t cover myself by snitching and I couldn’t lie; I never was a liar. So dancing Trooper Moody in circles was really a dress rehearsal for the state police major crime unit, which the cops themselves, I noticed, called the major case squad.

They arrived at last, a young, cleancut couple in plainclothes who looked like poster children for the FBI, Sergeant Arnold Bender and Trooper Marian Boyce. They listened to Oliver’s report, then ordered him to rig lights at the death site. The woman, Boyce, went into Rita’s house; Bender came to me.

“Why’d you move the body?”

“It was getting dark.”

“So what?”

“Animals would eat it.”

“Are you trying to be funny?”

“We’ve got raccoons, crows, turkey buzzards, weasels, rats, and mice.” I was winging the weasels; I had no idea if they ate dead meat, but everything else did, which I wanted to establish before this moving-the-body thing got out of hand and led to charges. I sensed blood in the air; money, sex, and beauty demanded arrests.

“You shouldn’t have moved the body.”

“I found a dead raccoon the other day. By the time I got a garbage bag so the health department could test it for rabies, crows had eaten everything but the fur.”

Bender sighed like a man who missed street corners. “Do you remember how the body looked? Before you moved it?”

“I saw a huge hole in the guy’s chest. His eyes were open. He was staring at the sky.”

“Was he on his back?”

“Yes.”

“Curled up? Spread out?”

“Spread out. Like he’d laid down to look at the sky.”

We walked to the site. Bender shook his head at the crushed grass. “Try to remember, Mr. Abbott, did it look to you like he crawled there, wounded? Had he come far?”

As he’d fallen on his back, even though he’d been shot from behind, I assumed he had probably staggered, caught his balance, then collapsed backwards. But that was Bender’s department, so all I said was, “No. I got the impression he hit the deck, dead.”

“Which way was he lying?”

“Head up toward the woods. Feet facing where we are now.”

“Did you hear shots?”

“No.”

“How’d you happen to find him then?”

I turned around and pointed at the tower. “We were in the top of the turret, looking out that win

dow. See that square opening? We saw his hair.”

“His hair?”

“It was shining in the sun. We went to investigate.”

“Why?”

“It’s Mrs. Long’s property. She saw something out of place. I thought it was a deer lying dead.”

“Why dead?”

“They don’t lie down in the evening. It looked like a white tail. So I figured it was dead.”

“You some kind of hunter?”

“My uncles were hunters. They taught me how to get along in the woods.”

“What were you doing in the tower?”

“Drinking champagne.”

“You got a thing going with the lady?”

“No.”

“Trooper Moody tells me you’re covering for her.”

“Trooper Moody should stick to speeding tickets.”

Sergeant Bender was half Moody’s size, but he had the state police stare, which he gave me full force. “Trooper Moody informs me you did time.”

“I served my time. I’m not on parole. You are way out of line.”

“I got a dead man, apparently shot. You moved him. When my lieutenant reads my report he’s going to ask, Why didn’t you bring the jailbird in?”

“My false-arrest suit will be based on two facts: First, I was charged with a white-collar crime; second, when whatever happened to that poor guy happened, I was grilling burgers for three hundred people at Town Hall.”

“You got some kind of problem with Trooper Moody?”

“Oliver has a problem with me.”

“Why?”

“Ask him sometime. If you want a good laugh.”

“Does Mrs. Long know the dead man?”

I had deliberately not asked her, so all I had to do was answer, “She called him Ron.”

An elderly diesel Mercedes chugged into the drive, decanting Dr. Steve Greenan, who served as one of the part-time assistant medical examiners for the county. Largely retired, he was a tall, white-haired, handsome man whose big shoulders had begun to slump with age. He trudged our way, seeing the yellow tape; Sergeant Bender ran to intercept. I followed, passing Oliver, who was stringing extension cords from the house.

FrostLine

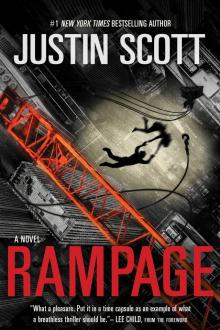

FrostLine Rampage

Rampage McMansion

McMansion Mausoleum

Mausoleum HardScape

HardScape The Shipkiller

The Shipkiller StoneDust

StoneDust