- Home

- Justin Scott

FrostLine Page 7

FrostLine Read online

Page 7

“Move it,” he shouted.

I turned off the ignition.

He strode nearer and recognized the Olds. “Get the hell out of here, Ben.”

“The man’s drunk. He can’t defend himself.”

“Move it!”

“I’m a witness.”

“Say what?”

“You’re beating up an unarmed citizen. I’m a witness.”

“I’m telling you once more, get the hell out of here.”

“Can’t do that, Ollie.”

***

Handcuffed together in the back of Ollie’s cruiser, charged with DWI (Dicky) and obstructing justice (me) we took the opportunity to review in low tones Dicky’s father’s problems with Henry King. Blizzards of paper had struck the Butler farm, courtesy of King, Inc.’s legal staff. For a while Ira Roth had shoveled him out, but now he was busy with a murder trial.

Worse than the paper blitz was King’s helicopter.

“Son of a bitch is buzzing the house,” said Dicky.

“You mean when he takes off?”

“He whips right over the house. You know what it sounds like to Pop? Sounds like he’s back in Vietnam. Woke up last night screaming some door gunner’s going to blow him away by mistake.”

“Does it happen often?”

“Too often. He’s getting pissed,” said Dicky. “He’s got a slow fuse, but the helicopter’s really bugging him.”

“Does he think they’re still watching him?”

Dicky looked at me, his face just visible in the instrument glow from Ollie’s dashboard. “Nobody’s watching him.”

“I wondered….What about the phone taps?”

“Maybe Pop’s a little extra suspicious, if you know what I mean. Not his fault, the way that son of a bitch treats him.”

“Shut up back there,” growled Ollie.

“Fuck you,” said Dicky, which was even stupider than me interfering with a trooper on a dark road. Without even slowing the cruiser, Ollie whipped the Mag light around in a backhand sweep. It crunched into Dicky’s head, scattering lens, batteries, halogen bulb and Dicky onto my lap. I felt for his pulse.

Ollie drove a couple of miles in silence. Finally he said, “You jailbirds have gotten kind of quiet.”

“I think you killed him, Ollie.”

“Bullshit.”

But he stopped the car, turned the lights on and had a look. Dicky stirred. Ollie slapped his face. Dicky fended him off, groggily. A huge purple bruise was radiating from the point of his cheek bone.

“See that bruise, Ollie?”

“Looks like another assault charge for old Dicky.”

“I’ll make you a one-time offer, Ollie. Take us back to our vehicles. Drop the charges. We won’t file a complaint. But if you take us into Plainfield, you’re looking at a year in court.”

Ollie had reptile eyes—dirty windows on a dull soul—but when warring with Newbury’s resident state trooper, it paid to remember that reptiles have prospered long on the planet.

“You threatening me, Ben?”

“I’m threatening you with misery,” I said. “You may beat it, but you’re going to spend a lot of time in court.”

I could almost see him wince at the thought of all those days indoors. “My sergeant’ll back me all the way against a pair of jailbirds.”

“You watch this ‘jailbird’ put on a suit and tie and smile at that jury….Besides, after a fight like that, will your sergeant back you next time? And let’s not forget Dicky’s false arrest suit.”

The reptile blinked.

***

Henry King got lucky too.

The dry spring made digging his lake a piece of cake. And then, in mid-July, just after they finished pouring the dam, Newbury got inundated with a week of rain that saved the farmers and filled King’s twenty-acre hole in the ground to the brim. This called for a celebration: the first week in August, printed invitations summoned all who were anybody to a gala christening of “Lake Vixen.”

I was surprised I got one. I must have been on the “Newbury’s First Families” list, because I sure hadn’t made the distinguished service list—not after botching King’s assignment to make peace with “that crazy old farmer.” Surprised, but glad. I hadn’t seen Julia Devlin since March and the one time I managed to dream up an excuse to drop by Fox Trot she and King had just lifted off in King’s helicopter.

At our next Tuesday afternoon tea I asked my Aunt Connie if she would like to drive up to the party with me.

“I’m not going.”

We were ensconced—as we had been weekly since I was eight years old—in the alcove contained by the bay window of her dining room. A warm breeze tugged the sheer curtains and wafted perfume from her rose garden.

“You don’t need an invite. Come as my guest.”

“‘An invite’?” she echoed, a combative glint in her eyes.

Her eyes are clear as glass, and stony blue when she gets feisty, which is most of the time. “I wonder,” she said, “about a person who would kidnap a verb when there exists a perfectly serviceable noun. To encounter one in my own family comes as something of a shock.”

“Sounds to me like you’re put out because you didn’t get an invitation.”

Connie’s manner, her bearing, and her standards reflect the sort of breeding that lost currency when World War One turned our Republic into a superpower. In addition, she possesses an innate kindness, what she would call in another person, Christian decency. But nothing obliges her to suffer fools gladly. Especially foolish nephews who forget that when men like Henry King court social acceptance in Connecticut, they had damned well better court Connie Abbott.

“Of course I received an invitation.”

“If you’re worried about standing around in the sun, I’ll run you home whenever you want. Though, from what I saw of the place, you can expect every comfort, including cool shade for the generationally challenged.”

I looked for another thin smile. But she was through with word games, and suddenly deadly serious: “I am not going to Henry King’s party.”

“Why not? I saw people you know. Wills the younger asked for you, backhandedly.”

“That horse’s behind.”

“So why aren’t you going?”

“For the same reason that any decent American with a memory longer than two weeks would not go. Even that loathsome video couldn’t conceal the fact that Henry King’s prevarication, treachery and arrogance cost the lives of thousands of American soldiers and God alone knows how many Vietnamese.”

“You’ve been talking to Mr. Butler.”

There are over a hundred Butlers in Newbury, but she loves the town the way a girl loves her dollhouse, and knew precisely which Butler I meant.

“Farmer Butler was wounded three times in Vietnam. Unless he suffered total brain damage—or is pathologically forgiving—I should imagine he’d like to punch his new neighbor in the nose.”

Should have talked to her before I went up there last March with my foot in my mouth.

“You know, King told me his feelings about the war and—”

Color rose in Connie’s cheeks.

“At best he was as out of touch with reality as the Soviets were in Afghanistan. At worst, he was motivated by a thirst for power.”

“Well, he admitted to doubts and—”

“He’s a brilliant self-promoter, Benjamin. Don’t be fooled. He saw years ahead of his competitors that the power that modern communications took away from the State Department would fall into the hands of an individual who spoke for the president. He was ready with a catcher’s mitt.”

“I’m not saying I bought into everything he believes, and I don’t know that much about the war, but I do think, relatively speaking—”

“I think it was Dr. Johnson who said, ‘When a moral relativist comes to dinner, I count the spoons.’”

***

I trie

d again the morning of the party. I found her reading the Times in her old-fashioned garden and I asked whether she had become a little more open-minded on the subject of Henry King.

“If I were that open-minded, my brain would fall out of my skull.”

“Let me ask you something. Would you prefer I didn’t go?”

“I can’t make that decision for you.”

“But what would you prefer?”

Connie thought about it. Finally, she said, “Go. When children fight their elders’ wars we get the Middle East.”

She did not go so far as to tell me to enjoy myself, though she did agree that King had lucked out with a perfectly beautiful day. A Canadian high-pressure system had slipped into the region under a crisp blue sky and the light was so pure that every painter in the state could dream of being Constable.

I banished the Olds to the barn and fired up the 1979 Fiat Spyder 2000 my mother had left when she moved back to her farm. The roadster, a rich Italian shade of British racing green, had been a love gift from my father. But Mom was too shy to drive something so “flashy” around Newbury. So its body was in mint condition, the engine barely broken in. Top down, reflections of trees undulating darkly on its shapely hood, it conveyed me in splendor appropriate to a lake-christening at Fox Trot.

Julia Devlin was the first person I saw. She was guarding the gate with a guest list and party smile and made a vastly better first impression than the Chevalley boys. She looked sleek in a sleeveless blouse. Her long arms rippled with a hint of muscle and her skin tanned by the summer sun. A Liberty floral skirt fell straight to her sandals. The filmy cloth, slit to her knee, hinted at legs as sleek as her arms, and I found myself hoping it would be the sort of party where everyone threw off their clothes and jumped into the lake.

“I like your car,” she greeted me.

“Nice to see you again,” I greeted her.

She smiled welcomingly. “And you are Mr…?”

Oh, wonderful. “Ben Abbott,” I helped her. “Real estate. Last March?”

“Of course. Drive on up the drive. There’s valet parking.”

“Are you stuck on gate duty all day?”

“I’m not stuck. I get to meet our guests while they’re still sober.”

“How about I bring you a glass of champagne after everyone arrives?”

“Oh, that’s nice. But I’m afraid they’ll be dribbling in all afternoon. Have a nice time.” Her eye drifted to her clipboard. “Mr. Abbott.”

The phrase “struck out” seemed inadequate.

Henry King’s lake, first visible when the drive emerged from the gentrified woodlot, was big enough to be blue. It was a startling sight that tore the eye from the new house, taming that structure and somewhat reducing its enormousness. Yet another example of landscape designers pulling overblown architects’ irons out of the fire.

A gigantic bright red hot air balloon was soaring above the house, tethered to a windlass in the motorcourt. The high school kids parking cars told me it was to show Mr. King’s guests Fox Trot’s just-completed landscape design. A prancing fox adorned the bag.

“Ben!”

I looked up.

Newbury’s first selectman leaned from the wicker passenger basket waving a champagne bottle, which, when our smiles met, she slipped between her lips. An on-again-off-again “item,” to use Henry King’s word, Vicky and I were still off—thanks to transgressions on my part, and a new, less-forgiving attitude on hers—and the tenderly ministered champagne bottle was a message: suffer.

“Let down your hair.”

Vicky had the hair for it, yards of beautiful Rapunzel tresses curled and heaped and framing her delicate features like a baroque picture frame carved of chestnut. But it was Tim Hall, my lawyer and Vicky’s ever-hopeful beau, who instructed the balloon’s operators. The winchman dragged the balloon out of the sky and I clambered into the basket. Tim looped a steadying arm around Vicky’s waist. The burner roared and belched fire and we floated swiftly into the blue, whisking over the house’s slate roof.

Fox Trot lay under us, the strict geometry of the house and gardens in orderly contrast to the sprawling farms and woods, and the whimsically natural shore of the lake. The field north of the lake had been planted in lawn, the lower ground to the south left wooded. The dam at the far end was still bright with raw concrete. Over the spillway bowed a bridge that looked like enterprising burglars had helicoptered it in from Central Park.

It was darned near perfect. The only flaw, if one could call it a flaw—and those who felt art must concede something to fate would regard it more benevolently than control freaks—was the long, narrow pasture that cut, to use King’s word, into the manicured lawns like a knife. A rusty knife, as Mr. Butler had been using it to dump old refrigerators and tractor tires.

***

Seeking out my host and hostess, I bumped into friends from Newbury—Scooter and Eleanor MacKay, Ira Roth, Al and Babs Bell, and some of the country club crowd, appropriately dazzled—and various megabucks New Yorkers, including a couple of wary erstwhile colleagues from the Street, who looked afraid I’d ask them for a job.

Bertram Wills, King’s tame former secretary of state, greeted me vaguely. He was hovering near Mrs. King and looking grandly statesmanlike in a splendid linen suit. When Al Bell, whose namesake ancestor had married into social prominence after inventing the telephone, asked whether Henry King had negotiated the weather with the Pope, Wills gripped his side and chuckled, “Very funny, Al. Very funny.”

King’s retired CIA pet was there, too, muttering orders to the waiters from the side of his mouth. Sunlight wasn’t kind to Josh Wiggens: Scotch was bloating his chiseled face. I gave him a nod and was not surprised when he snubbed me.

I was surprised, however, to see the handsome butler King had fired last March. “Welcome back, Jenkins.”

I offered my hand. He returned his stiff bow. “Thank you, sir, Mr. Abbott.” With the caterers running things, he looked edgy as a general reliant on his predecessor’s colonels.

“I’m a little surprised to see you here. That was a memorable exit.”

Jenkins gathered himself with brittle dignity. “Madame insisted I return.” Tearing reverent eyes from “Madame,” who was flitting about prettily, he beckoned a waiter to refill my glass.

I climbed to the highest terrace where Henry King was surrounded by guests. He looked tired, pouchy under the eyes, and somewhat overdressed in a blue suit. He seemed nervous. His eyes were skipping everywhere, like an impresario counting the house. His champagne glass, filled with sparkling water, slipped from his hand. An agile waiter caught it and returned it gracefully, only to be chewed out for spilling a drop on the diplomat’s sleeve.

King remembered me, if not fondly. His greeting, a pointed inquiry about Connie’s health, made it clear that my invitation had come on my aunt’s Blue Book coattails. But it was far too happy a day for my presence to blunt his pleasure. Everything he had ever worked for had come together in Lake Vixen. No expense had been spared to celebrate, no generosity overlooked.

Servants were legion, passing hors d’oeuvres in quantities to satisfy Catherine the Great and delicacy to delight Marie Antoinette. Had the July rains not filled his lake, it would have brimmed from spillage of champagne: magnums of Veuve Clicquot—no mere Moët at Fox Trot—poured liberally by staff wandering the terraces; more magnums stationed strategically about the walks in shaded ice buckets in the event a glass went suddenly dry while a guest was lost in a boxwood maze or deep in the sunken garden. But I do not suggest that my New England eye was offended by ostentation, for the choice of Veuve Clicquot, like the lovely food and the imaginative balloon ride, seemed determined by generosity as much as display.

Mrs. King proved to be generous, too, introducing me to her friends, including the wife of the British Ambassador, whom I had been coveting from a distance. Tall and slim, she had silver-gray hair and the level gaze of a woman who

enjoyed what she wanted.

I think we surprised each other. We were both reading Trollope that summer—The Way We Live Now—I for the first time, Fiona for the third. She had children about to enter university, and when the subject of little Alison came up we discussed horses. Occasionally she checked that the ambassador was happily occupied.

“Do you know the young woman talking to my husband?”

“Vicky McLachlan. Our first selectman. Would you like to meet her?”

“No. No. He looks content.”

Smitten was the more accurate word, but here I was smitten too, so who was I to talk?

Henry King bustled over repeatedly with guests in tow. He seemed miffed that I was monopolizing a star guest, and finally inquired, “Has Mr. Abbott sold you a house, yet, Lady Fiona?” proudly stressing the very “Lady” that she had invited me to abjure.

“Why ever would he?” she asked coolly.

“Didn’t he tell you he’s a real estate agent?”

“Of course not.”

But King was persistent—and no slouch at the manners-as-power game—dragging personage after personage over to be introduced. The subtext, I began to scope out, involved British patents for a ceramic engine. The Japanese wanted to manufacture it. The British preferred to establish the factories in Britain, with Japanese money.

Aware that for the wife of the ambassador this was a working party, I started to ease out of it, to make room for an Osaka industrialist accompanied by a New York publicist whose name had been synonymous with 1990s gluttony. Fiona laid her hand on my arm and smiled a clear message that I was free to leave her if I cared to spend the rest of the afternoon with ordinary women.

The thump-clack of an old diesel Farmall interrupted King’s introduction of yet another industrialist. “Oh look!” the publicity lady cried.

The bright red tractor came rolling down the long, narrow, sloping pasture that Mr. Butler had leased from Mr. Zarega. Mr. Butler was driving, dressed in blue overalls and a dirty tee shirt, his long hair flying in the breeze. The flatbed trailer he was towing was piled high with green silage.

FrostLine

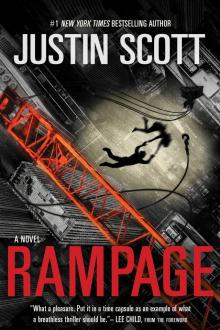

FrostLine Rampage

Rampage McMansion

McMansion Mausoleum

Mausoleum HardScape

HardScape The Shipkiller

The Shipkiller StoneDust

StoneDust