- Home

- Justin Scott

FrostLine Page 4

FrostLine Read online

Page 4

I kept my hands down and my voice conversational. “Congratulations on getting out. I was just heading up to see you.”

“Oh, yeah?”

“I got a bottle of dago red in the car.” He liked red wine a lot. It was ruining his face, the fair Irish skin veined like a much older man’s.

“Oh yeah?” he said at last. I could see the heat fading in his eyes as they filled with the broader surroundings. They settled on my car, which was sitting inside King’s gate, like a prisoner. “Hey, you’re still driving the Olds.”

“Pink keeps it going for me. Repairs don’t cost much more than leasing a new BMW.”

Dicky’s eyes flared toward movement. Dennis was trying to stand up. “Stay there,” I told him. “Catch your breath.” And to Dicky I said, “Can I ride up with you?”

Dicky looked over the carnage as if he would miss it. Finally, as Dennis lay back, holding his face, he shrugged and headed for my car. “I’ll get the wine.”

He came back through the gate with the bottle tucked under his arm, and opened his fly.

Dennis said, “What the hell’s he doing?”

“Reminding you who won the fight.”

“He jumped us.”

“Yeah, I saw. Guy’s got no morals.”

Dicky cleared his zipper and pissed on Henry King’s wrought iron like a wolf marking territory.

“The son of a—”

I told my cousin to shut up.

Dicky Butler took aim at King’s shiny black Chevy truck. Dennis tried to stand. I didn’t let him.

Dicky marked the Chevy, zipped up and swaggered to his own truck. Dennis tracked him, eyes burning. The broken nose make him sound whiny as a bitter old man.

“I’m going to get my gun and shoot ’im.”

“If you do you’ll go to prison and make your mom real unhappy—you up to driving?”

“Where?”

“Emergency room. Get your nose taped.”

“I gotta watch the gate.”

“Albert’s waking up. He can watch the gate. Take my car—don’t worry, you can tell Mr. King you tripped over a stump.”

I checked out Albert’s eyes to make sure that they were focusing in unison. Then I climbed into Dicky’s pickup. He popped the clutch, scattering mud on King’s new four-by, and tore up the road.

“What was that all about?”

“Son of a bitchin’ neighbor’s bugging my old man.”

I’d have bought deeper into his filial concern if I didn’t know the hoops he’d run his father through for the past twenty years.

“I went down to see him. Your cousins tried to stop me.”

“Just doing their job.”

“I fired ’em.”

Blood was trickling from his nose, so I reached out with a handkerchief. “Here. You’re bleeding.”

Dicky recoiled. “Don’t touch me!”

“Easy….Easy. You’re bleeding. I’m just handing you a handkerchief. Here.” Again I extended my handkerchief. He took it gingerly, and pressed the linen to his nose. Only then did I realize he was wearing deerskin gloves and had been the whole time.

He drove fast, beating the old truck, whipping it through the switchbacks that worked their way up the mountain, skidding the rear end, spinning the tires on the muddy surface of the frozen ground. A month of this treatment and his father would need a new one he couldn’t afford.

“What’s the neighbor doing to your father?”

“Trying to force him off our land. Bugging him with lawyers. Said if he didn’t sell Pop would be living in a tent. Rich bastard.”

“What were you going to say to him?”

“I am going to say it to him: Leave my old man alone or I’ll be down there kicking ass and taking names.”

“Dicky, you threaten a guy with his kind of money he’ll have lawyers on you like paint. Before you know it you’ll be right back inside.”

“Hey, I’m not on parole. I’m clear as you are. They can’t touch me.”

“Dicky,” I said very firmly. “I worked on Wall Street. I know these people. They buy what they want. They can touch you.”

“What do you care?”

“King asked me to talk to you and your Dad. He doesn’t want to keep fighting and I don’t think you guys do either, do you?”

“Shit, man, I don’t care. But Pop, he just wants to be left alone. Is that too damned much to ask? Man just wants to pay his taxes and be left alone.”

“Is he behind?”

“Behind what?”

“On his land taxes.”

“Ask him.”

Henry King would put the screws to him when he caught wind of that.

“It ain’t fair,” Dicky went on. “Ain’t fair a guy reaches that age and gets pushed around. Especially a guy who served his country.”

Some of the most ardent patriots I’d known I’d met in prison. But I heard in Dicky’s voice a strange and unexpected note of compassion.

“Pop suffered, Ben. What you and me been through’s nothin’ compared to the shit he saw in Vietnam. We can’t begin to know what he went through. You know what I’m saying? For him thirty-forty years ago is like yesterday.”

“I know what you’re saying. But I never heard you say it before.”

“Yeah, I never thought it before. Seeing a lot of things different now.”

I had a feeling he was going to tell me next he got religion. It happened. Lots of people inside found God.

“Ben, the shit I put that poor bastard through. And blaming him for my mother cutting out….Who the hell knows why she left.”

Now I wondered if the prison shrink had gotten hold of him. But it wasn’t that either.

He said, “I don’t even know what happy women are thinking. Who knows what the sad ones want?”

My responses were down to near-silent grunts. Just enough to get him back to his father’s land feud.

“I figure my mother was one of the sad ones, right?”

“Couldn’t have been happy leaving a little kid.”

“You realize my father raised me all by himself?”

We emerged from the scraggly woods hugging the road. He stomped the brakes. The truck stopped on a little bump of a rise from which we could see the weather-beaten house and barns of the Butler farm. A rare flash of humor lit his face. “’Course Pop had some help from the state.”

“Dicky, you seem a little different.”

He turned off the engine. We sat quietly for awhile, gazing out at the gray monotones of a Connecticut farm in winter. If I ever wondered why farmers moved to town, graphic evidence lay before me. Mud everywhere. Cows bunched unhappily in bare pastures. Rickety buildings scattered like the crash site of a gigantic wooden airplane.

“I got the AIDS, Ben.”

“What?” He had spoken so softly I hoped I’d heard him wrong.

“I got the AIDS.”

“Oh, Jesus…I’m sorry. What do you mean? HIV-positive? Or…”

“Positive. Ready to roll.”

“Not full blown?”

“Not yet.”

“Well, that’s something. Any luck you got some time.”

“Get it tomorrow. Get it next year.”

“Next year they may get a cure. Already, they’re slowing it down. Right?”

“Feel like I swallowed an alarm clock. Wait for that baby to wake me up….Wake up and die, Dude.”

I didn’t ask how he’d got it. We both knew the opportunities inside. Or maybe he’d picked it up years ago between convictions. Either way, it was his business. But there was something that was my business. Mine and everyone else in town.

“You jumped when I reached with the handkerchief. You know it’s transmitted by blood.”

“Yeah, I know.”

“You can’t go around punching people, Dicky, it’s like shooting them with a gun.”

He held up his gloved hands. “I’m no

t a goddammed killer, Ben.”

“Yeah, what would have happened if you duked it out with me and I cut a knuckle on your tooth?” I shivered at the thought. “Jesus Christ, Dicky. You scare the hell out of me.”

“Yeah, well no one’s ever knocked out my teeth. I’m too fast. They taught me so good in Cheshire I could have fought pro.”

I looked at him. I was angry. And scared silly by the near miss of potentials and possibilities. “Dicky, they taught you damned good footwork. And that’s a nice fast left you got. Dennis Chevalley hadn’t a clue. But you ever fight a real boxer you’ll lose a tooth every time you throw a right.”

“Think so?”

“I know so. And you’ll kill the poor bastard in the process. The gloves aren’t enough. You’re a weapon. You got to give up the fighting.”

“Hey, I didn’t start it. I was just going to talk to that rich son of a bitch running the gears on Pop.”

“Treat fighting like it’s booze and you’re a drunk. Give it up.”

“Maybe I should get a girlfriend? Kill her instead?”

“You could do worse than a girl who’s a friend. Just don’t sleep with the poor woman.”

Dicky shrugged. “I got used to not getting laid inside. Maybe I’ll pretend I’m inside….” He grinned again, with little humor this time. “Life’s a bitch.”

I had to agree.

“And then I die.”

We stared out the windshield for a while and finally I asked, “Have you told your dad?”

“Not yet.”

The cows started drifting toward the barn.

“Here he comes.”

Dicky opened the window, leaned into the cracked side-view mirror, and began wiping the blood off his face.

Chapter 4

Mr. Butler—I could never call him by his first name; even in my own maturity, less than twenty years his junior, he would always be Mr. Butler—plodded out of the barn with a bale of hay on his shoulder. I couldn’t see his face from where Dicky and I sat in the truck, but anyone in Newbury would have recognized him by his long hair swinging in the sun.

The cows closed in on him, their breath white in the cold air.

“Want to give him a hand?”

“Not in that mud.” Dicky held up one of his stitched cowboy boots by way of explanation.

A huge old yellow dog plodded at Mr. Butler’s heels. DaNang, the last of three golden retrievers named for places Mr. Butler had been wounded in the war. “How the hell old is DaNang?” I asked Dicky.

“Old.”

He finished wiping his face. “Don’t tell Pop what happened.”

“You got a knot on your head.”

He inspected it. Protruding from his bristly hair where he had butted Albert, it looked like a good start on a rhinoceros horn. “Shit.”

“Tell him you banged it getting out of the truck.”

Dicky stuffed my bloody handkerchief in his pocket and started the engine. As he put it into gear he looked at me with an unspoken question.

I said, “You can tell who you want. They won’t hear it from me.”

“Appreciate it.”

“Do me a favor. Last thing you and your dad need is a war with Henry King. Will you let me see what I can work out?”

Dicky thought it over. “Just don’t bulldoze him, Ben. I won’t let nobody do that.”

I promised I wouldn’t, and we drove into the farmyard.

Mr. Butler opened the hay bale with a wire cutter, scattered it with a few practiced kicks as the cows closed in, and climbed through the fence. Dicky’s cleanup job didn’t fool him for a second. His face fell when he saw the knot.

I said, “Hello, Mr. Butler,” and extended my hand. “I don’t know if you remember me. I’m Ben Abbott.”

“I remember you. Heard you took over your dad’s business.” (True—eight years ago.)

He took my hand in a work-calloused palm and squeezed politely, his eyes drifting to Dicky. “Whatcha looking at?” asked Dicky.

“What happened to your head?”

“Hit it on your truck.”

I could see he wanted to believe him. And he might have talked himself into it if Dicky’s nose hadn’t chosen that moment to resume bleeding. “You’re home three hours and you’re in a fight.”

“I was doing it for you.”

“For me? You want to do something for me, see if you can stay out of jail long enough to sue for that false arrest. You think getting locked up again’ll help our case?”

Dicky said, “Tell him, Ben.”

Ordinarily, I excuse myself from family arguments. Entering in is a wonderful way of making mortal enemies of an entire clan. But Henry King had wedged me right into the middle of this one. Still, if I was going to ignore my instincts, the least I could do was cover my back. So I said, “Dicky, get lost. Let me talk to your dad.”

Dicky grabbed the bottle from the truck and stalked up to the house. His father looked mildly astonished that his son hadn’t taken a poke at me for ordering him around.

“I’ll explain,” I said.

He watched Dicky until the kitchen door slammed. Then he stared at me a long moment. “Come on, let’s get out of the wind,” he said, and led me into the barn. There was a torn and bent webbed folding chair set in the open wall that faced the corral where the cows were eating. He sat heavily in it and indicated a rusty tractor seat welded to an old milk can for me. I pulled it close and sat beside him where we could watch the animals or turn to face each other.

“What’s up?” he said. He leaned over to pick at the hay stalks that had stuck to his muddy boots, and his long hair draped his face. We were looking west, into the sun. It made the gray look almost silver. But when he raised his head, the same light was cruel, exposing hard years. His mustache was gray. Deep lines scored the skin beside his hawk nose. His eyes were dull.

“What are you going to tell me Dicky can’t tell me himself?”

“It’s not about Dicky. At least not directly.”

“Who’d he fight?”

“Dennis and Albert Chevalley.”

“They’re working for King.”

“He went to see King. They tried to stop him.”

“Sons of bitches.”

“They’re a couple of dumb kids. They do what they’re told.”

Mr. Butler’s shoulders sagged. “Ben, I don’t want no trouble with Chevalleys. I got my hands full with that ’sucker down the hill.”

“I guarantee you they won’t tell a soul that one guy smaller than them kicked both their asses simultaneously.”

Mr. Butler smiled. “No, I guess they won’t.”

“So that’s not a problem,” I said. “The problem is King.”

“What’s it to you?”

“He asked me to intercede.”

“Intercede?”

“Make peace.”

“Why you?”

“Hell, I don’t know, Mr. Butler. I thought he wanted to talk real estate. Instead he got this idea in his head that I’m some kind of local fixer.”

Butler smiled again. “Maybe he heard how you found poor old Uncle Pete.”

“He wasn’t that lost.”

“Troopers couldn’t find him.”

“I had more time on my hands.”

The Butler family—unduly impressed by my oni service—had hired me to track down a forgetful elder who had disappeared. “He had already been found,” I reminded Mr. Butler, who was distantly related to Uncle Pete. A waitress from New Milford had found him.

“Heard they got engaged,” said Mr. Butler.

“I wouldn’t be surprised.”

“Shows there’s hope for all of us.”

“Anyhow…”

“Anyhow, I don’t see what business it is of yours.”

“Hey, I can only help if both sides want me to. I promised King I’d help. Are you interested? Or do you want to keep on fighting?”

“I’m not fighting. He’s fighting. I was doing fine ’til the son of a bitch started throwing his weight around.”

“How do you mean?”

“I bet he told you he didn’t understand the pasture lease. Said he didn’t realize how close it was to the house, because he was a city boy. Did he?”

“That’s what he said.”

“Bullshit. He saw it. He just figured he’d plow me under with lawyers. Blow me off. Screw the dumb farmer.”

“Well, he knows now he was wrong about that. I think he feels like a damned fool. Won’t be the first time a city guy got his wires crossed.”

“He looks at me and I see in his eyes if I disappeared from the face of the earth, he’d be a happy man. Well, I ain’t disappearing. This is my home. Been home to my family since my grandfather bought it.”

Most of Newbury’s Butlers had migrated up from Bridgeport after World War One.

“And when I die, it’ll be Dicky’s home—I know what you’re thinking. You think when I die Dicky’ll sell. Well, that’s his business. When I’m dead and gone I won’t give a damn. But I’m not dying and I’m not going anywhere. I’m going to live my life here. And you can tell that son of a bitch down the hill I just passed my VA physical with flying colors. They told me I’ll be farming at ninety.”

“Congratulations.”

“Damn straight—Christ, I’m twenty years younger than Uncle Pete. Maybe I’ll meet a waitress, too….Wouldn’t mind having a woman around here, again. I been alone a long time….You’re not married, are you?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Seem to have a bad habit of falling in love with the wrong woman.”

“Tell me about it. Jeez, Dicky’s mother was a looker….You know, Ben. If that sorry son of a bitch had just come up here, man to man, and asked, neighbor to neighbor, could we work out something with that lease—hell, I wouldn’t have spit in his face. But he sent goddammed yuppie lawyers. I set DaNang on ’em. Then he sends a pair of washed-up bureaucrats: Bert Wills from Middlebury? And some jerk spook drummed out of the CIA giving me a song and dance about the lease isn’t good. Ira Roth wrote that lease. Goddamned Devil couldn’t break it.”

FrostLine

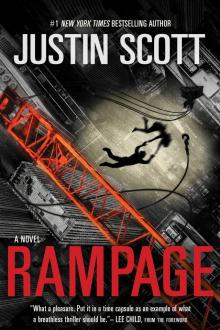

FrostLine Rampage

Rampage McMansion

McMansion Mausoleum

Mausoleum HardScape

HardScape The Shipkiller

The Shipkiller StoneDust

StoneDust