- Home

- Justin Scott

FrostLine Page 5

FrostLine Read online

Page 5

Mr. Butler liked Ira because back when he had hope that Dicky would straighten out, Ira had twice had charges thrown out of court.

“Wills and what’s-his-name—?”

“Wiggens?”

“Yup, Wiggens. They treated me like garbage. What if I were the sorry ’sucker they thought I was? They’d have scared me into giving up what was mine.”

“How’d you happen to lease it? It’s a funny-shaped little piece.”

“I didn’t want the damned field. Crazy old Zarega insisted.”

“Why?”

“Oh, I don’t know. The bear died. He wanted cows around.”

“The bear died?”

“Of course he died. Must have been hitting forty. So I leased it, strung some fence, and I made sure to run a few head in. Old Man Zarega would shuffle out on his walker, lean on the fence, watch ’em for hours. He was a neat old guy. Sorry I didn’t get to know him sooner. But I was pretty crazy the first ten years I was home. Lived like a goddammed hermit.”

“Tell me if I’m out of line. But it sounds like you wouldn’t miss it if you leased it back to King.”

“You looking for a commission?”

“It’s how I make my living, Mr. Butler. You farm. I broker property.”

“I hope you’re doing better than I am.”

“I’ve seen better years.”

“Thank God I got my disability. Only way a dairy farmer can make a living is get shot for his country—you know people pay more for Perrier water than a quart of milk?”

“I know that people send yuppie lawyers when they should have sent real estate agents.”

“Bullshit. He should have come himself. But he’s always been a guy to make other people do his dirty work—”

He cocked his ear, suddenly tense. A second later I heard it too, the heavy thudding of a helicopter. It got closer and louder until it shook the rafters, screamed over the tin roof, and thundered toward Fox Trot.

Mr. Butler sat rigid, hands clasped in double fists, strings of muscle trembling in his neck. When the sound had died entirely, he spoke in a cold and bitter voice.

“They’re using you, Ben. I thought you were better than this.”

The helicopter had derailed what had felt like an increasingly cordial conversation. DaNang raised his huge head and gazed at me inquiringly. I asked for both of us, “How do you mean?”

“Didn’t they teach you any history at Annapolis?”

“History? Some. Mostly naval.”

“Ben, I personally knew five guys who wouldn’t be dead if that son of a bitch hadn’t been grandstanding in Paris. There’s twenty thousand of us would still be alive today.”

“You mean Vietnam?”

“Yes, I mean Vietnam, you goddammed draft dodger.”

Spit flew. He had screamed the accusation. The dog stood up, and positioned himself close to Mr. Butler. Something unpleasant rumbled in his chest.

I shifted my feet to move quickly, and tried to keep it light.

“I was five years old, Mr. Butler. I had a kindergarten deferment.”

He worried his mustache with his work-blunted fingers. Then he expelled a whoosh of breath that hung in the cold like a comics balloon. “Oh, yeah. Yeah, musta been thinking of somebody else. You’re Dicky’s age, right?”

“Yes, Mr. Butler.”

“Lotsa times I still think he’s a kid. You guys aren’t kids.”

“No, sir.”

“Time blows my mind. Sometimes I don’t know what year it is.”

I said, “My mother’s father farmed over in Frenchtown. He used to say seasons count more than years.”

“You know anything about the war?”

“Not a lot.”

Mr. Butler stared at his cows, who had demolished the hay. DaNang settled at his master’s feet. When Mr. Butler finally spoke, in his soft voice, he sounded normal again, almost professorial in his measured statement. “King egged Nixon on. Who do you think dreamed up, ‘I’m not going to be the first American president to lose a war’? We’d already lost. Johnson knew it. Goddammed MacNamara knew it. Us grunts knew it.

“I was a demo man. That’s how I got my license for blowin’ ledge. Want to know what I was blowing in Nam? Microwave relay towers. Our microwave relay towers. The Viet Cong took territory, they left the towers standing, figured they’d use ’em after they won.

“King and Kissinger made their careers at the Paris peace talks. Page one news every day it dragged on. King encouraged Kissinger’s fantasies: You know, their nineteenth century tin-soldier politics. What did they call it? Had some fancy name for it. Real politics. Something like that. Jesus H. Christ, Ben, we’re talking about eighteen-year-old flesh and blood. We weren’t tin. Not us, not the poor gooks either.”

And just in case I didn’t fully comprehend how the Vietnam War affected the lease, he added, “So when Henry King sends lawyers, and flunkies, and real estate agents creeping up my hill, he’s just doing what he always did: treating ordinary people like tin soldiers. Tell him no, Ben. Tell him no I won’t lease it back. Tell him I won’t sell an acre. Tell him he can’t run pipes on my land. And tell Henry King he better stop bugging me or one of these days I’ll bug him back.”

“How do you mean, ‘bugging’ you?”

“He’s got people spying on me.”

“Spying?”

“They’re watching me. I’ll be out in the field and get this feeling I used to in the war—when someone’s lining a bead on you.”

“Watching you? What for?”

“Saw the sun glint on binoculars—or a sniper scope.”

“Who’s watching you?”

“Could of been a sniper scope.”

“Mr. Butler, if someone were aiming a sniper scope up here alone on the hill, you’d be dead, wouldn’t you?”

“They ever find me with my head blown off, you’ll remember I told you.”

“Have you actually seen people on your property?”

“They been tapping my phone. It’s clicking.”

I said, “SNET’s lines are pretty old up the hill. I get clicks on Main Street. But these lines gotta be thirty years old. Mr. Butler, I think there are two questions here. Who are ‘they’ and why would ‘they’ watch you and tap your phone?”

“Trying to scare me.”

“To make you sell the lease?”

“Tell Henry King the United States Army taught this tin soldier demolition. Tell him if he gives me any more trouble I’ll blow his dam and make his fancy new lake look like a crater on the moon.”

As mildly and conciliatorily as I could, I said, “Mr. Butler, I’m not going to repeat that and I don’t think you should, either. That’s a pretty serious threat.”

“Get off my land.”

He stood up, balling his fists. DaNang lurched purposefully to his feet, menacing as a bitter old prize fighter sunk to dance club bouncer for drinks and tips.

***

Finishing-school posture, bright eyes, and thick, curly white hair made Great-aunt Connie Abbott look considerably younger than her many years. Days she felt well, it was hard to believe that on a school trip to the White House she had met President Herbert Hoover. And challenged him to help the victims of the Crash. Two years later she helped establish soup kitchens in every city in the state.

I invited her over to watch Henry King’s A&E “Biography,” hoping for an historical perspective on how to handle him. It seemed a fairly tame puff piece, with little taste for exposing villainy. Actions that had propelled a significant portion of the population into the streets thiry-five years ago were labeled “controversial.”

Five minutes into it, Connie was perched like a sparrowhawk on the edge of her chair. And at the first shot of burning flags, she couldn’t contain herself. “How dare they impugn the patriotism of the protestors!”

King had spent his early career lurking. Still young in the Vietnam years, he

was ever at the elbows of Kissinger, Haldeman, Erhlichman, Nixon, his bright face alert, body poised like a runner in the blocks. But after the war was over, he stood taller; and now the eager faces were behind him. Of course by then, Connie smiled, his former mentors were all in prison or disgrace.

As the Republicans shuffled off in leg irons, King had finessed himself into the Carter Administration, then bailed out by resigning publicly—“Sanctimoniously,” Connie snapped—over the Iran hostage crisis in time to join the Reagan Act. That’s when he began to look like money. His suits became handmade; his transport, corporate jet.

Around that same time, his harsh Brooklyn voice evolved into the vaguely English tones Wall Street guys pick up when they parachute into the London office. He spoke more slowly, too. He was probably trying to concentrate on his new accent, but it made him sound very important, as if, Connie noted acidly, his elocution teacher had painted his larynx with gravitas.

By the time Bush I took away his White House pass, the transformation from scholarship student was complete. Henry King sounded as wise and sure as a Harvard professor who published regularly and was endowed with an immense family fortune and friends in the highest places.

Henry King Incorporated hit big and soon he enjoyed all the perks of a top CEO—private jets, personal helicopters, full floors of the best hotels—combined with all the courtesies due a visiting head of state—Third World military salutes, palace luncheons, and presidential dinners.

“Have you noticed that young brunette?” asked Connie.

“Julia Devlin. I met her up there.”

“There’s something odd about her.”

“There was something about her. I wouldn’t call it odd.”

The pleasures of a world-class world-beater included servants, flocks of aides, and luscious protege-personal assistants. Since he had gone into business for himself, Julia Devlin traveled everywhere with him like the Emperor’s concubine.

“What do you think?” I asked Connie when the DVD ended.

“If a vulgar, self-serving, unprincipled betrayer of the public trust rates a reverent biography on television, then our country has gone to Hades in a handbasket,” she said, and went home without thanking me for the show.

Clues to handle him? Hard to tell. The latter part of the bio, which ballyhooed Henry King Incorporated’s contribution to world trade and everlasting peace, showed a man surrounded by admirers who were convinced that if they could only be near him some of his immense power and wisdom might rub off.

People so attended lost their sense of humor. The only way to negotiate with them was to possess something they wanted very much and feared they couldn’t steal. Mr. Butler did not enjoy that position—a disadvantage of which he was ignorant. That put the local “fixer” between a fast-moving rock and a grim and bitter hard place.

***

Henry King declared he was surprised to see me back so soon. I said No thank you to mulled cider, but he insisted. It was the King of Norway’s recipe.

It was late afternoon the next day, with a cold night looming. His library was lit splendidly by dying daylight and a bright orange crackling fire of applewood. Josh Wiggens, the CIA man, had brought the cider, which he appeared to have been sampling since lunch, and seemed barely to notice when King dismissed him on the flimsy pretext that so-and-so in Washington was awaiting his call.

Julia Devlin stuck her head in the door. I smiled. She smiled back and said to King, “Excuse me, shall I sit in with you?”

“I told you, no,” King snapped at her.

She held her face blank, as she closed the door.

Alone at last, cozied up on the chesterfield, he repeated, “You have come back so soon.”

“It didn’t go well.”

“Why not?”

I related my conversation with Mr. Butler, minus references to Vietnam on the theory that King, too, might have a sore spot there, and if he didn’t, then he wouldn’t understand a word Butler had said.

Turned out he didn’t understand a word I said either. Angered, he sent the Harvard professor on sabbatical, and I got a taste of what Julia had to work with.

“What the hell did you tell him?”

“I told him,” I repeated patiently, and more politely than his manner deserved, “that you asked me to intercede to try to make peace between you.”

“What about the lease?” King shot back.

“As I told you a moment ago, the good news is, he doesn’t really want the pasture. He only took it to please Mr. Zarega.”

“What the hell did Zarega want with a dollar a year?”

“Mr. Zarega wanted to look at cows.”

“Are you joking with me?”

“When Mr. Zarega’s bear died,” I explained, evenly, “he wanted animals around. Mr. Butler obliged by shooing some cows into that pasture.”

“I’m next door to a lunatic asylum.”

I smiled, hoping he had a sense of humor after all. But King did not smile back. Instead, he raked me with that laser gleam of intelligence. “Something’s missing, here. What did you leave out?”

“Vietnam. He’s a vet. He blames you for the war.”

“He’s not the only man who suffered in Vietnam.”

“He blames you for them, too.”

King sighed. “I did not start the Vietnam War.”

He stood up and walked to a shelf and ran his hand along the books. “But there are eighty volumes on this shelf that blame me for Vietnam. And my friends in publishing warn me that the revisionists have only begun to stir. Decisions I agonized over thirty years ago—and still torment me—have spawned a vigorous cottage industry.”

King returned to the couch and sat heavily. “If those writers and professors and reporters and memoirists and historians refused to believe that when the United States bombed the North, the enemy came to the table—and when we stopped bombing, they left the table—then how can I convince the farmer next door that I did my best to stop the killing?”

“I can’t answer that. All I know is he experienced it up close, and he’s not ready for any revisionists.”

“Hundreds of thousands came home and resumed their normal lives. They don’t look back. What’s different about him?”

“He’s not hundreds of thousands. He’s just one guy.”

“Is this my penance? I’m supposed lay back and open my knees?”

“Laying back would be sufficient.”

“It’s not fair,” he said. “I served my country, too. I served it as I knew best.”

“Look, I was five years old. I can’t judge either of you. All I know is you’ll be neighbors a long time. Maybe, someday, you can agonize together over a drink.”

King did not look convinced. “What’s next?” he demanded. “What’s your next move?”

“I just told you. Sit tight. Let him cool down.”

“How the hell long is that going to take? I want my lake finished by summer. I want my guests here. Do something.”

I stood up to go. “The sooner you stop pushing him, the sooner he might come around. My advice is leave him alone. No lawyers. No more offers. Just let it lay awhile….And you might tell your helicopter pilot to find another landing path. I thought we were getting someplace, until he buzzed the barn.”

“Am I supposed to pay you for this advice?”

“No charge. I didn’t deliver.”

“That’s for damned sure. I suppose you expect me to call you back when he’s cooled down?”

“He set his dog on me, Mr. King. I take that as a signal he doesn’t want me back.”

“If that damned dog comes around here, I’ll have it shot.”

I leaned close and made him look me in the eye. “Don’t shoot his dog or you’ll answer to me.”

“To you?”

“And let me give you some more advice.”

“Keep it.”

“Mr. Butler is your neighbor. He’

s not going away. And whatever you do, don’t rile his son.”

“I’ve got people who can handle his son.”

“I wouldn’t count on that.”

“I don’t mean those bozo cousins of yours.”

No surprise that the camera on the gatehouse had recorded the fight.

“I still wouldn’t count on that. The State of Connecticut has tried and failed for twenty years.”

King tried to have the last word. “My people aren’t bound by their rules.”

By his “people,” I supposed he meant that his retired spy could call up hitters on a per diem basis. Or maybe former national security advisors had Secret Service protection.

“Diplomacy by different means?”

“Every war has a winner, Mr. Abbott.”

I went home wishing I’d done a better job.

Chapter 5

The following Saturday I got a phone call from a frantic Mrs. Henry King. I could barely hear her over the noise of a revving chainsaw.

“Mr. Abbott—Ben—can you come up here? Henry’s really upset. The farmer’s sawing trees.”

I said, “If you’re outside on a cell phone, go inside and close the door.”

The racket ceased with a bang. “Can you hear me, now?”

“Much better. Is he on his leased land?”

“Henry’s going crazy. I’m afraid—”

“Where’s Josh Wiggens?”

“He took the Chevalley boys shopping.”

“Shopping?”

“For spring work clothes.”

There was a picture: the patrician security man herding those two through the Danbury Fair Mall like bulls in search of china.

“How about Julia Devlin?”

“London.”

“Is Mr. Butler’s son with him?”

“I don’t see him.”

Pray you don’t, I thought.

“Please come. He’s killing our beautiful trees.”

“Twenty minutes. Open the gate and—”

“Henry, don’t,” she cried.

I ran for the car, and made Fox Trot in fifteen. The gate was open, the driveway spikes latent. The motor court and parking area were empty, the offices dark, the workmen off for the weekend.

I jumped out of the car and squished through the mud toward the whining, growling din of Mr. Butler’s chainsaw. It stopped abruptly. There was a sharp crack and, as I rounded the house, a triumphant, “Timmmmberrrr!”

FrostLine

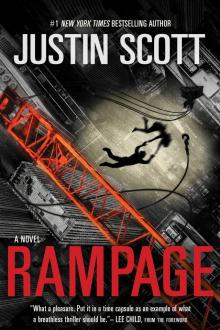

FrostLine Rampage

Rampage McMansion

McMansion Mausoleum

Mausoleum HardScape

HardScape The Shipkiller

The Shipkiller StoneDust

StoneDust